Dear readers, apologies for the glacial pace of new posts recently. I’m currently working on edits and re-writes for the English version of our book, which we hope to have released in the fall, and until that’s wrapped up the blog will be in something of a state of suspended animation. We appreciate your understanding. More blog posts and updates on the book will be forthcoming in a few weeks. Until then, may this monster tide you over. – Charlie

In spite of myriad traumas and forced relocations over the same period, for the past 600 years the Korean peninsula’s center of power (the southern half’s at least) has always gravitated to the same few square kilometers between Gwanghwamun Gate and Bukhan Mountain. Since 1392, when the Joseon dynasty’s founder, King Taejo, moved the capital from Kaeseong to Hanseong (as Seoul was then known), it’s been this auspicious site, backed by mountain and fronted by water, that has beat the rhythm the rest of the nation has marched to. For centuries the seat of the Joseon kings and currently the residence of the president, it’s arguably the most important neighborhood in the country.

In spite of myriad traumas and forced relocations over the same period, for the past 600 years the Korean peninsula’s center of power (the southern half’s at least) has always gravitated to the same few square kilometers between Gwanghwamun Gate and Bukhan Mountain. Since 1392, when the Joseon dynasty’s founder, King Taejo, moved the capital from Kaeseong to Hanseong (as Seoul was then known), it’s been this auspicious site, backed by mountain and fronted by water, that has beat the rhythm the rest of the nation has marched to. For centuries the seat of the Joseon kings and currently the residence of the president, it’s arguably the most important neighborhood in the country.

Delving into that importance should start with the area’s preeminent attraction, Gyeongbok Palace (경복궁).

Exit 5 connects the station directly to the interior of the palace grounds, but to experience Gyeongbokgung properly it’s better to U-turn out of Exit 4 and enter through Gwanghwamun Gate (광화문), the south-facing and principal of the palace’s four main gates. Gwanghwamun is flanked by haetae, the mythical dragon-bear-like creatures thought to protect against misfortune, and watched over by palace guards in brilliant red, marigold, and cobalt silks and fake goatees. Some of them stood guard with scimitars or pikes; others with long poles on which fringed colorful banners ruffled in the breeze, just above the heads of the tourists massed around them, cameras raised to catch the changing of the guard ceremony that was just beginning. The rumble of a drum snuck through the throb of traffic passing by out front. Like so much else of Korea’s royal heritage, Gwanghwamun was damaged and relocated numerous times throughout its history, but it’s currently back in its original position and looking beautiful, if a bit fresh-out-of-the-box, after a recent restoration. The massive stone and wood gate has three gigantic doors; the central one was reserved for the king, the others for military and civilian officials, respectively.

Once inside, visitors find themselves in a large outer courtyard where, if you can ignore the tour groups and the hordes of middle school students on class trips, you might just notice that the setting is truly majestic, with Inwang Mountain (인왕산) looming up in the west and the pyramidal Bukhan Mountain (북한산) forming a nearly symmetrical and nearly perfectly centered backdrop behind the throne hall. After buying tickets, trying on palace guard uniforms, or picking up an audio guide, stepping through the first inner gate deposits you on the grounds of Joseon’s greatest palace.

Once inside, visitors find themselves in a large outer courtyard where, if you can ignore the tour groups and the hordes of middle school students on class trips, you might just notice that the setting is truly majestic, with Inwang Mountain (인왕산) looming up in the west and the pyramidal Bukhan Mountain (북한산) forming a nearly symmetrical and nearly perfectly centered backdrop behind the throne hall. After buying tickets, trying on palace guard uniforms, or picking up an audio guide, stepping through the first inner gate deposits you on the grounds of Joseon’s greatest palace.

Meaning ‘Palace Greatly Blessed by Heaven,’ Gyeongbokgung was founded in 1395 and was the king’s primary residence for the first 200 years of the Joseon dynasty. Originally consisting of nearly 500 buildings, it was largely destroyed during the late 16th century invasions of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, but while the daimyo’s forces were busy laying waste to so many other structures, it was actually Koreans who were largely responsible for Gyeongbokgung’s obliteration. Seeing an opportunity amid the chaos to wipe out the records of their identity, the city’s slaves set the palace alight, turning its slave registers to ash.

Gyeongbokgung was then left to languish for nearly three centuries (Changdeokgung (창덕궁) replacing it as the king’s main residence) until 1867 when a perhaps imprudent reconstruction occurred, nearly bankrupting the country. Its restored glory didn’t last. When it annexed Korea, Japan stripped the royal halls of their furniture and artwork and left only ten buildings standing. Restoration finally began in 1990 and has been ongoing ever since. Today many structures have been rebuilt or repaired, but what exists today is still only a fraction of the palace at its height.

The complex today can be roughly divided into thirds: its central axis and east and west flanks. The central axis, running north from Gwanghwamun toward Bukhan Mountain is where the palace’s most important structures can be found, and the next gate leads to Gyeongbokgung’s heart, Geunjeong Hall (근정전) and its surrounding courtyard. Reconstructed in the 1860s and renovated in 2001, Geunjeongjeon was the main throne hall, where the king attended to affairs of state and held celebrations. The footpath leading up to it is flanked by twelve pairs of stone markers, each bearing a different rank and marking the spot where court officials would stand during formal events, military officials on one side, civilian officials on the other. It’s also thronged with visitors on any given day and is one of the only places in the city where, after five-plus years living here, I feel utterly like a tourist and just a general oddity. I hadn’t been there more than a minute or two when the first of several groups of middle school students came giggling up to me asking to take a picture together. I asked where they were from, Seoul kids being way too blasé about foreigners to get excited about some random white dude. They were from Jeonju. I told them I loved Jeonju. Shrieks. OK, poto, poto. Bh-wee! Click. Tank you! Bye!

Chinese tour groups in matching red hats; guides with pennants held aloft like some kind of weird 21st century parallel to Joseon standard bearers; tourists going from camera to guide book and back; Korean students roaming in large, loud packs – the hubbub is such a contrast to the imagined former solemnity and order of the place that it can be hard to conceive of Geunjeongjeon as the former seat of a kingdom, but the building itself still has the ability to make all the commotion going on around it seem peripheral. Though dwarfed by the modern city’s skyscrapers, it is still the country’s largest wooden structure and must have been truly imposing when first constructed. The hall has a brilliantly painted two-tiered roof, and a large stone staircase leads up to the hall’s doors. Standing on Geunjeongjeon’s landing and gazing out towards the front of the complex puts the viewer at an elevation nearly even with that of the courtyard gate’s roof, a perspective of sheer power.

Chinese tour groups in matching red hats; guides with pennants held aloft like some kind of weird 21st century parallel to Joseon standard bearers; tourists going from camera to guide book and back; Korean students roaming in large, loud packs – the hubbub is such a contrast to the imagined former solemnity and order of the place that it can be hard to conceive of Geunjeongjeon as the former seat of a kingdom, but the building itself still has the ability to make all the commotion going on around it seem peripheral. Though dwarfed by the modern city’s skyscrapers, it is still the country’s largest wooden structure and must have been truly imposing when first constructed. The hall has a brilliantly painted two-tiered roof, and a large stone staircase leads up to the hall’s doors. Standing on Geunjeongjeon’s landing and gazing out towards the front of the complex puts the viewer at an elevation nearly even with that of the courtyard gate’s roof, a perspective of sheer power.

Most gazes were pointed in the opposite direction, however, as visitors rotated up to the main doors, peered in, snapped a photo or two, and then left, someone else taking their place. Inside, the focal point is the king’s red throne, regal but also understated by royal standards. Behind the throne is a painting of the sun, moon, and five mountain peaks, symbolizing the universe and the king’s supreme power. Ceremonial tables and fans lined up on either side of the room and, in a candid display of what modern life at the palace is, a trio of electricians futzed with some faulty lighting.

Behind Geunjeongjeon the next facility along the central axis is Seojeong Hall (서정전), a reception hall where the king met officials or held meetings, complete with smaller versions of the throne and its backing painting. Storage rooms occupied the wall out front, and auxiliary buildings on either side were fitted with low tables, study materials, and folding screens depicting cranes and mountains. Seojeongjeon opens onto Gangnyeonjeon (강년전) and Gyotaejeon (교태전), the king’s and queen’s living quarters, whose sweetest feature is Amisan (아미산), a flowered and terraced slope at the quarters’ rear. Embellished with decorative stonework and chimneys and accentuated by a solitary leaning pine, Amisan is symbolically a natural garden for immortals.

Behind Geunjeongjeon the next facility along the central axis is Seojeong Hall (서정전), a reception hall where the king met officials or held meetings, complete with smaller versions of the throne and its backing painting. Storage rooms occupied the wall out front, and auxiliary buildings on either side were fitted with low tables, study materials, and folding screens depicting cranes and mountains. Seojeongjeon opens onto Gangnyeonjeon (강년전) and Gyotaejeon (교태전), the king’s and queen’s living quarters, whose sweetest feature is Amisan (아미산), a flowered and terraced slope at the quarters’ rear. Embellished with decorative stonework and chimneys and accentuated by a solitary leaning pine, Amisan is symbolically a natural garden for immortals.

Beyond the royal couple’s quarters was once an area for concubines, though those buildings are now gone. Instead visitors next arrive at the transfixing Hyangwonji (향원지). Surrounded by flower bushes, a slender wooden footbridge crosses this artificial pond to the manmade island in the middle, where Hyangwonjeong Pavilion (향원정) sits, blending in perfectly with the mountain slopes in the distance.

Beyond the royal couple’s quarters was once an area for concubines, though those buildings are now gone. Instead visitors next arrive at the transfixing Hyangwonji (향원지). Surrounded by flower bushes, a slender wooden footbridge crosses this artificial pond to the manmade island in the middle, where Hyangwonjeong Pavilion (향원정) sits, blending in perfectly with the mountain slopes in the distance.

In 1873 in Korea, rebelling against your parents wasn’t as simple as getting a tattoo or majoring in philosophy, so when Gojong wanted to assert his independence from his father, the powerful Prince Regent Heungseon Daewongun (흥선대원군), he built Geoncheonggung (건청궁), a palace within a palace just north of the pond. (Way to make a statement, bro, to say, ‘You know what, old man? I don’t need you. I can do things on my own. I’m moving out!’ and then move out into the back yard.) Uniquely, Geoncheonggung was built in the style of a yangban household so that it’s basically an enormous hanok. In 1887 it also became the first place in the country to be fitted with electric lights, courtesy of the Edison Electric Light Company.

Most famously, however, Geoncheonggung was the scene of one of the Joseon dynasty’s most tragic episodes, as it was here, on October 8, 1895, that Gojong’s wife, Empress Myeongseong, was murdered by Japanese assassins. One of Joseon’s most influential female figures, Myeongseong oversaw much of the country’s modernization and opening to the West and, as such, was a major source of headaches for the Japanese, who had their own designs for the peninsula. Following his wife’s death, Gojong fled the palace for the Russian legation, never to return. Although 65 men were charged in connection to the crime none were convicted, and within two decades Korea was a Japanese colony. Geoncheonggung was demolished in 1909, the Japanese Governor-General Art Gallery built in its place. It was only restored in 2007.

The last structure along the central axis is the site of Gwanmungak (관문각), which was built in 1873 to enshrine the king’s portrait. Demolished and then rebuilt in 1891 under the guidance of the Russian architect A.S. Sabatine, it was the first western building in the Joseon dynasty’s history.

Gyeongbokgung’s eastern flank has two remaining complexes. The first is Donggung (동궁), the ‘Eastern Palace.’ This was the residence of the Crown Prince, located here because the lucky young man was seen as a rising sun. Restored in 1999, Donggung was divided into two sections: Jaseondang (자선당), where the prince lived with his consort, and Bihyeongak (비현각), where he attended to state affairs.

Really, though, probably the best thing about Donggung was its proximity to the royal kitchens, which were just to the north. At the time of visiting, however, the Sojubang (소주방) was closed for restoration, though a few tourists were having their picture taken in front of a large poster that let visitors know that this was the setting for the popular TV show ‘Jewel in the Palace’ (‘대장금’).

A visit down the western flank begins with Sujeongjeon (수정전). Originally called Jiphyeonjeon (집현전), the ‘Hall of Worthies,’ this was where Hangeul was invented, according to the on-site plaque. Directly behind it is the complex’s other highlight, Gyeonghoeru (경회루), a two-story pavilion overlooking another manmade pond and two square islands. The largest elevated pavilion in Korea, this was where Joseon kings made it rain, hosting royal banquets, entertaining foreign envoys, and boating on the pond. It’s also a particularly symbolic structure – the three bays at the center representing heaven, earth, and man; its twelve outer bays standing for the months; and the 24 outermost columns signifying the 24 solar terms.

Gyeonghoeru is one of the most photogenic spots in Seoul, and dozens of visitors were lined up posing along the south shore. As long as camera angles were kept high enough this was fine, but if they tilted downwards all those Facebook profile pics-to-be would have been spoiled by the thick layer of green-brown scum that covered much of the pond’s southeast and most popular corner, so thick in some spots it looked as if the surface had solidified. Just above the pond in a little noticed corner was a banner for MLEKOREA saying ‘Working on improving water quality!’ Uh, work harder, guys.

If you’d like to see Gyeonghoeru up close, the only way to do so is to sign up for one of the special tours that are run from April to October. Tours can be booked through the Gyeongbokgung website and are limited to 80 people per day.

Beyond the pavilion is an empty space where closer examination reveals the outlines of buildings that are no longer there. Past this, and just west of Hyangwonji is the Janggo (장고), the former storage area for fermented pastes and sauces. Reconstructed in 2005, it now displays storage jars from various regions around the peninsula. Past the Janggo are the Chinese-influenced Jipohkjae (집옥재) and Hyeopgildang (협길당), a library and reception hall for foreign envoys, and the Palujeong pavilion (팔우정).

Beyond the pavilion is an empty space where closer examination reveals the outlines of buildings that are no longer there. Past this, and just west of Hyangwonji is the Janggo (장고), the former storage area for fermented pastes and sauces. Reconstructed in 2005, it now displays storage jars from various regions around the peninsula. Past the Janggo are the Chinese-influenced Jipohkjae (집옥재) and Hyeopgildang (협길당), a library and reception hall for foreign envoys, and the Palujeong pavilion (팔우정).

The most remote corner of Gyeongbokgung houses Taewonjeon (태원전), the royal coffin hall, where funeral ceremonies were once performed. Like much else in the palace, the buildings were removed by the Japanese and restored only in 2006. In the interim, the area served as a station for presidential guards, located as it is just across the street from Cheongwadae. Though not particularly exciting, Taewonjeon is easily the quietest spot on the palace grounds, and the only place where you can clasp your hands behind your back, stick your chin out, and strut down the porticoes, imagining yourself a haughty court official without risk of being caught. If, you know, that’s your thing.

The grounds of Gyeongbokgung are also home to two museums. If you arrive via Exit 5, just behind the blooming red, purple, and fuchsia flower bushes is the National Palace Museum of Korea (국립고궁박물관).

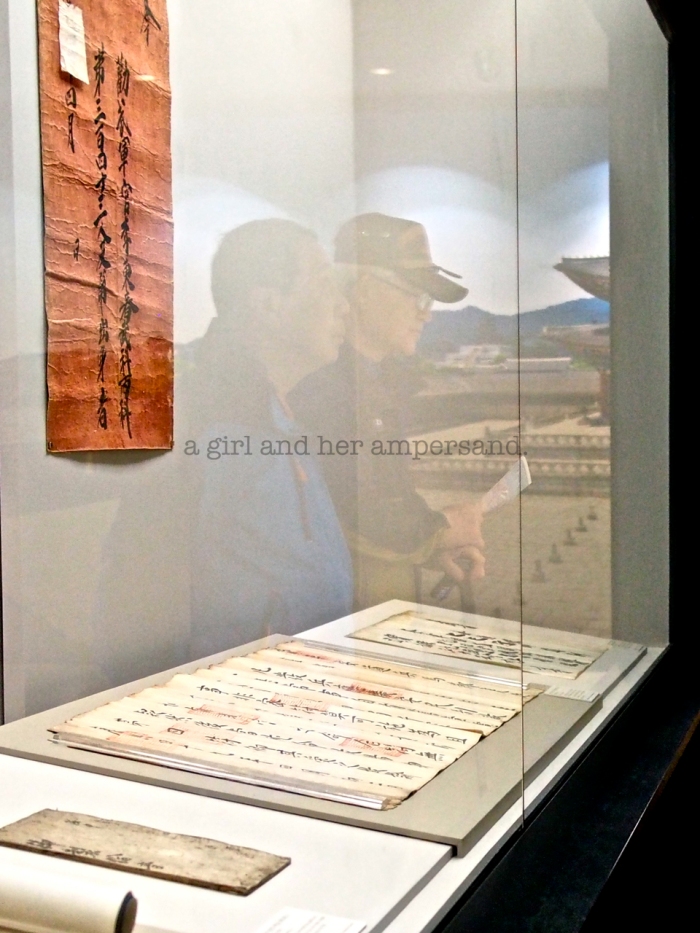

The National Palace Museum does not extend back into any of the older dynasties on the peninsula, limiting its focus to the Joseon dynasty alone, though it holds over 40,000 artifacts from the period. Exhibits start on the second floor with a family tree of the dynasty’s monarchs and exhibits of royal seals, edicts, and what were, essentially, a young prince’s school supplies: brushes, ink stones, and Confucian texts. Another section is devoted to the five palaces – their histories, their architecture, their symbolism. The small stone figures seated on the eaves at the corners of palace rooftops turn out to be mostly characters from the Chinese tale ‘Journey to the West’: the Monkey King, Pig Monster, Half-Water-Demon, and, at the front, Reverend Xanzang.

Proceeding downstairs, the first thing visitors encounter is the Royal Caddy, which Emperor Sunjong was chauffeured around in, and right after this you learn about how, after births, the royal placentas were buried in jars. Exhibits proceed through a section on the Daehan Empire and its introduction of foreign technologies, and there’s also a display of the very Westernized interior of its Royal Court.

Proceeding downstairs, the first thing visitors encounter is the Royal Caddy, which Emperor Sunjong was chauffeured around in, and right after this you learn about how, after births, the royal placentas were buried in jars. Exhibits proceed through a section on the Daehan Empire and its introduction of foreign technologies, and there’s also a display of the very Westernized interior of its Royal Court.

The basement floor was labeled in the museum brochure as having four sections – Royal Court Paintings, Royal Court Music, Royal Procession, and Joseon Science II – but only the last of these actually existed. A sign said that one area was closed temporarily for a special exhibition, but this was confusing as the actual current special exhibition was up on the second floor. The science room contained some exhibitions on medicine and sundials, but most of it was devoted to the Self-Striking Water Clock (자격루). Invented by 장영실 (Jang Yeong-Sil) during King Sejong’s reign, it was regarded as the pinnacle of scientific achievement at the time, though looking at it now one’s first reaction is, ‘All that, just to know the hour?’ Like early computers, the thing is room-sized, and was essentially a Rube Goldberg device in a box, using dripping water, floats, steel balls on tracks, and levers to make a series of little wooden dolls strike either a drum or a gong. Regardless of its gimmicky appearance, however, it was accurate enough to be the official Joseon timepiece, regulating the striking of the city bell in Bosingak.

Despite some interesting bits and pieces, the National Palace Museum is, overall, a disappointment. The building itself has a rather sterile feel to it, and exhibitions suffer from poor presentation. Type is often too small and ighting is often too low and poorly positioned, making the reading of information on displays difficult. Moreover, that lighting is usually provided by generic fluorescent tubes affixed behind opaque plastic covers, giving the artifacts a drab, washed out appearance. On top of that, the museum is sorely lacking in English information, to say nothing of Japanese or Chinese, of which there is practically none, an oversight that is especially befuddling when you take into account its location on the grounds of the country’s number one tourist attraction and the fact that its purpose is to show off the grandest parts of Korea’s history.

Much better is the other museum on the premises, the National Folk Museum of Korea (국립민속박물관). Exhibitions begin outside, with several wooden and stone jangseung (장승), village guardian totems, examples of phallic and vaginal stones where people would pray for a son, and an ox-powered rotary millstone used for grinding grain. There is also Ochondaek (오촌댁), a hanok dating from 1848 that was moved to the museum grounds from Gyeongsangbuk-do. Visitors can enter the middle-upper class home and check out the various accoutrements on display inside: large storage jars topped by woven straw lids, pink silk pajamas hanging from a bar in a bedroom, a long, thin pipe on a low table.

Further back is A Street to the Past (추억의거리), with recreations meant to give visitors an idea of city life through the decades. In the Way Back When division, shops for horsehair hats, silk, and bamboo sit next to an old lever-operated streetcar, its burgundy paint peeling. Representing the 1970s and 80s are comic book shops, electronics shops, and a barber shop where a diagram of brand new 1970s hair styles hangs alongside a picture of a family of pigs. There’s also an old classroom where students’ briefcase-like school bags have been left on the seats and, on the chalkboard, a list of 떠든아이 (noisy kids) and 모범생 (model students) is written down. Shape up, 신상출! Good job 차염심! Next door to the classroom is a photo studio where, from 1 – 4 p.m. you can try on school uniforms of the era.

Further back is A Street to the Past (추억의거리), with recreations meant to give visitors an idea of city life through the decades. In the Way Back When division, shops for horsehair hats, silk, and bamboo sit next to an old lever-operated streetcar, its burgundy paint peeling. Representing the 1970s and 80s are comic book shops, electronics shops, and a barber shop where a diagram of brand new 1970s hair styles hangs alongside a picture of a family of pigs. There’s also an old classroom where students’ briefcase-like school bags have been left on the seats and, on the chalkboard, a list of 떠든아이 (noisy kids) and 모범생 (model students) is written down. Shape up, 신상출! Good job 차염심! Next door to the classroom is a photo studio where, from 1 – 4 p.m. you can try on school uniforms of the era.

Occupying the building that the National Museum of Korea once did, the main part of the National Folk Museum is divided into three sections. First up is History of the Korean People, which touches on the Paleolithic and Neolithic eras before skipping quickly forward to the Gojoseon (고조선). Far superior to the Palace Museum, the NFMK has extensive English explanations, some Japanese and Chinese, good lighting, and some gorgeous animated film. These are utilized to showcase Gojoseon and Goryeo (고려) painting and pottery, the development of Hangeul, and a slideshow of photos taken by Hermann Gustav Theodor Sandor in the first decade of the 1900s, juxtaposed with photos of those same places now.

Occupying the building that the National Museum of Korea once did, the main part of the National Folk Museum is divided into three sections. First up is History of the Korean People, which touches on the Paleolithic and Neolithic eras before skipping quickly forward to the Gojoseon (고조선). Far superior to the Palace Museum, the NFMK has extensive English explanations, some Japanese and Chinese, good lighting, and some gorgeous animated film. These are utilized to showcase Gojoseon and Goryeo (고려) painting and pottery, the development of Hangeul, and a slideshow of photos taken by Hermann Gustav Theodor Sandor in the first decade of the 1900s, juxtaposed with photos of those same places now.

Section two, Korean Way of Life, traces a typical rural village’s lifecycle through the seasons. In spring there was planting and foraging for wild roots. In summer, villagers spent their time weeding and fishing. Fall brought harvest, Chuseok celebrations, and home repair, and winter was for hunting, making kimchi, and fermenting soybeans.

Section two, Korean Way of Life, traces a typical rural village’s lifecycle through the seasons. In spring there was planting and foraging for wild roots. In summer, villagers spent their time weeding and fishing. Fall brought harvest, Chuseok celebrations, and home repair, and winter was for hunting, making kimchi, and fermenting soybeans.

Korean Life Passages wraps up the museum, and in this section visitors are walked through the major events in the life of someone of the yangban class (양반), the Joseon nobility. Beginning with dol, the first birthday celebration, it then continues through a young man’s education (Chinese characters, Confucian relations, astronomy) to the coming of age ceremony, when boys put their hair in a topknot for the first time. The next major event was a wedding (which was often the first time the couple actually met), followed often by civil service examinations, before, if they made it to old age, a large celebration was held on their sixtieth birthday.

Korean Life Passages wraps up the museum, and in this section visitors are walked through the major events in the life of someone of the yangban class (양반), the Joseon nobility. Beginning with dol, the first birthday celebration, it then continues through a young man’s education (Chinese characters, Confucian relations, astronomy) to the coming of age ceremony, when boys put their hair in a topknot for the first time. The next major event was a wedding (which was often the first time the couple actually met), followed often by civil service examinations, before, if they made it to old age, a large celebration was held on their sixtieth birthday.

There is also a small Children’s Museum (어린이박물관) attached to the NMFK where, at the time I visited, the special exhibition was all about communications. Don’t let the smiling telephones fool you, son. You gonna get educated here. Things start with an explanation of how signal fires were used to relay messages up and down the peninsula, the different kites used to transmit military orders, and how, in battle, drums were used to signal an advance and gongs to signal a retreat. You’ll also get brought up to speed on pre-Kakao pager shorthand. A primer:

There is also a small Children’s Museum (어린이박물관) attached to the NMFK where, at the time I visited, the special exhibition was all about communications. Don’t let the smiling telephones fool you, son. You gonna get educated here. Things start with an explanation of how signal fires were used to relay messages up and down the peninsula, the different kites used to transmit military orders, and how, in battle, drums were used to signal an advance and gongs to signal a retreat. You’ll also get brought up to speed on pre-Kakao pager shorthand. A primer:

11 – I want to walk beside you. (나란히걷고싶어.)

5858 – Oppa oppa! (오빠오빠!)

38317 – I love you. (사랑해.) (Type it into your calculator, turn it upside down, and learn German.)

When the Joseon dynasty was expired by the Japanese, the colonialists chose the same location for their point of control, building their Government-General Building in the area where Gwanghwamun now stands. After World War II the sovereign again Republic of Korea moved its leader’s digs into Gyeongbokgung’s backyard, where they’ve remained.

When the Joseon dynasty was expired by the Japanese, the colonialists chose the same location for their point of control, building their Government-General Building in the area where Gwanghwamun now stands. After World War II the sovereign again Republic of Korea moved its leader’s digs into Gyeongbokgung’s backyard, where they’ve remained.

Cheongwadae (청와대) – also known as the Blue House due to its distinctive blue roof tiles, which denote a seat of authority and were once reserved for kings – is the residence of the Korean head of state, and can be reached by walking north on either of the roads that parallel Gyeongbokgung. From the station, the most direct way is to U-turn out of Exit 4 and then turn left on Hyoja-ro (효자로). If you’ve been visiting the Folk Museum it’s quicker to go up Samcheong-ro (삼청로). If you go this route, be sure to make a quick detour to take in Dongsipjagak (동십자각), Gyeongbokgung’s southeastern watch tower. The tower’s stout, domineering stone base contrasts almost comically with its gracefully carved and intricately painted wooden upper portion. Development has separated Dongsipjagak from the palace walls it was once attached to, though, and it’s now marooned on a traffic island, making up close viewing difficult.

Outside the eastern palace wall on Samcheong-ro is a second wall, this one of tour buses parked nose to tail. I counted 31 as I walked north, most of them with signs in their windshields denoting which middle school or Chinese tour group they were ferrying around. As I rounded the bend onto Cheongwadae-ro (청와대로) the queue of buses ceased, pedestrian traffic lessened, and cops became noticeably more prevalent, though not oppressively so. One in reflective sunglasses and white gloves snapped off a crisp salute and gave me a cheerful ‘Annyeonghaseyo!’ as I passed by.

The Cheongwadae complex was much bigger than I had naively thought, though of course the only thing I had to base my judgment on was a gaze over a wall at the compound’s rooftops. Though the security presence was obvious, I had expected more cops and more very big guns of the sort that I saw only one carrying, slung casually across his chest as he ambled down the sidewalk. I’m sure there were security cameras all over tracking my every move, but the only surveillance I noticed was the occasional guy on a rooftop, looking at me looking at him.

It’s possible to exit Gyeongbokgung from its north gate, and if you do it puts you directly across from the main entrance to Cheongwadae, where a white gate adorned with the gold presidential phoenix seal separates the hoi polloi from the perfectly pruned shrubbery and those blue roof tiles, which, upon closer inspection, are actually more of a greenish, grayish blue. Behind the house Bukhansan forms an almost perfect equilateral triangle. When I arrived some police and secret service guys in dark suits, shades, and earpieces were milling about on the small plaza across from the gates, but they were greatly outnumbered by the Chinese tourists busy taking pictures of the president’s house and having their picture taken with the house in the background. Through it all the security staff was remarkably relaxed, intervening only occasionally to politely request someone to not take video footage.

If you approach the house via Hyoja-ro, at the Cheongwadae intersection Cheongwadae Sarangchae (청와대사랑채), will be on your left. Under reconstruction at the time of visiting, though most likely open now, it houses exhibits on Korean UNESCO World Heritage Sites, displays on major tourist attractions, and a mock presidential office. The plaza in front features a huge fountain – a large phoenix surrounded by groups of seated citizens – a pavilion housing a drum, and a few lone protestors and supplicants holding up placards pointed in the direction of the Blue House. Unusually for Korean protestors, the ones here were all silent, and the most consistent sound was the crackling speech coming through the secret service guys’ walkie-talkies and out of the portable speakers that tour guides wore in lanyards around their necks.

Opposite the plaza is the small Mugunghwa Park (무궁화공원), which was being used mostly as a bathroom break spot for Chinese tourists, who kept up a steady stream between their tour buses and the park’s restrooms. Among the benches and flower beds were two plaques, one displaying and explaining several paintings of scenic spots and Joseon councilors’ homes in nearby Bukhan Mountain, the other marking the former site of the house of 김항헌 (Kim Sang-heon), whom I’m utterly clueless about.

Opposite the plaza is the small Mugunghwa Park (무궁화공원), which was being used mostly as a bathroom break spot for Chinese tourists, who kept up a steady stream between their tour buses and the park’s restrooms. Among the benches and flower beds were two plaques, one displaying and explaining several paintings of scenic spots and Joseon councilors’ homes in nearby Bukhan Mountain, the other marking the former site of the house of 김항헌 (Kim Sang-heon), whom I’m utterly clueless about.

The street leading north from the park goes by the Vatican City embassy on the left (Hey, now you know.), and, on the right, Yuksanggung Shrine (육상궁). Unfortunately, there was no entry, and although a sign said that there was ‘restricted’ public access, considering that it’s on the grounds of Cheongwadae I have to imagine that that access is very restricted. Which was a pity, because from beyond the wall Yuksanggung looked stunningly gorgeous, with elegant red wood buildings and dazzling eaves climbing up a gentle hillside surrounded by trees.

Just as every evil genius needs their henchmen and every crooner their big band, every king and every president needs their supporting cast, and just as the main man’s (or, as is presently the case, woman’s) residence has hung about the same spot, so too has the domain of their ministers and ministries.

In the Joseon period, the street running south from Gwanghwamun was known as Yukjo-geori (육조거리), or the Street of Six Ministries, as it was on either side of the thoroughfare that the most important and most powerful government institutions were headquartered. Although the offices of the modern equivalents are much more diffuse, the government bureaucracy remains a distinct presence. U-turn out of Exit 6 and almost immediately you arrive at the Government Complex Seoul (정부서울청사). This large, rather anonymous building would look just as at home in Gangnam’s business district were it not for the dozens of white Korean flags on flagpoles along the roadside, the pairs of policemen standing at attention in glass booths near the entrances, and the lone ajumma protestor out front, placards strapped to her front and back, another held aloft over her head.

At the corner of Gwanghwamun Plaza (광화문광장), in the middle of which some workers were erecting a colorful temporary pagoda for the upcoming Buddha’s Birthday celebrations, I turned right onto Sejong-daero (세종대로). Fronting the plaza, just before the Sejong Center for the Performing Arts, is Sejong-ro Park (세종로공원). Although it has some flower beds and trees, this stone paved spot is more plaza than park. If you pause to look down, though, you’ll spot a plaque in the sidewalk noting that this was the former site of the Byeongjo (병조터), the ministry of defense in charge of recruiting military officials, managing weapons depots, and guarding the king during the Joseon period. Today, it’s where government employees take smoke breaks.

At the corner of Gwanghwamun Plaza (광화문광장), in the middle of which some workers were erecting a colorful temporary pagoda for the upcoming Buddha’s Birthday celebrations, I turned right onto Sejong-daero (세종대로). Fronting the plaza, just before the Sejong Center for the Performing Arts, is Sejong-ro Park (세종로공원). Although it has some flower beds and trees, this stone paved spot is more plaza than park. If you pause to look down, though, you’ll spot a plaque in the sidewalk noting that this was the former site of the Byeongjo (병조터), the ministry of defense in charge of recruiting military officials, managing weapons depots, and guarding the king during the Joseon period. Today, it’s where government employees take smoke breaks.

More current and ex-government facilities dot the streets south of the station. U-turn out of Exit 7 and the first street on your right is Saemunan-ro-3-gil (새문안로3길), also known as Hangeul-gaon-gil (한글가온길). As a sign on the corner says, gaon is a pure Korean word meaning ‘center,’ and this little street attempts to be something of a center for the celebration of the national alphabet. Close to its entrance is a small clock tower designed with colorful Hangeul letters, and at its far end are the headquarters of the Korean Language Society (한글학회). In between are a couple other commemorative sites devoted to linguists, neither of which I could find. I did, however, stumble across another sidewalk plaque denoting the former site of Jangheunggo Office (장흥고터), which stored and dispensed supplies to the Joseon palaces and their offices – the royal Staples, basically.

Next to Sejong-ro Park the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (외교부) was connected to the Government Complex via a skybridge, and further along the street passing underneath it was the Seoul Metropolitan Police Academy (서울특별시지방경찰청). The leafy streets, the office towers, the cafes, bistros, and restaurants – it could have been any business district in Gangnam or Yeouido or Euljiro were it not for the small telltale signs that one could easily overlook: the heavier than usual concentration of police, the high number of Korean flags, the less hurried mien of the local employees, secure in their government jobs. How secure? I saw one dude roll by on what I can only describe as the Future. Take a Segway, lose the vertical pole and handlebar, shrink the wheels and push them together so they fit in a black plastic chassis the size of a couple of stacked pizza boxes, and put a foot stand on either side and you’ve got what this guy was rollin’ down the sidewalk on, hands in his pockets, wondering what all the suckers around him were doing with those awkward leg things. I’m not making this up.

When diplomacy or war doesn’t work, what do you do? You pray to the gods.

Go straight from Exit 1 along Sajik-ro (사직로) to where it curves south and at the bend is Sajik Park (사직공원), which holds Sajik Altar (사직단), Historic Site No. 121, where sacred rites to the gods of land (Sasin (사신)) and grain (Jiksin (직신)) were held. The altars were constructed by King Taejo in 1395, one of the first structures built after he had moved the capital to Seoul, and together with Jongmyo, on the opposite side of the palace, Sajikdan formed the spiritual foundation of the Joseon dynasty. The complex originally consisted of the altars, buildings for ritual preparation, and the Sajikseo (사직서), a government office responsible for the altars’ maintenance, but after Japan colonized South Korea the buildings were removed and the rites forcibly discontinued in an effort to strip the capital of any of its vestiges of power. Only the two altars were permitted to remain; the rest of the grounds were turned into a park.

At Sajikdan’s entrance is the simple, three-bay Sajikdan Main Gate (사직단대문), Treasure No. 177. The current incarnation is a 1720 reconstruction, after the original was burned down during the 1592 Japanese invasions. It used to stand 24 meters forward of its current location, but was moved back twice in 1962 and ’73 for road construction. Sajikdan underwent restoration in 1980, and inside there are now outer and inner walls surrounding the altars, Sadan (사단) to the east and Jikdan (직단) to the west. The main entrance to the altars is on the north side, opposite a small playground (an innocuous continuation of Japan’s transformation of the park), though it and all other gates are closed, meaning visitors can only look at the altars from a distance. A better view can be had through the south gate or over the walls from the small hill on the west side.

In truth, there’s not much to see. A three-part stone walkway zig-zags across a broad lawn from the north to the west gate, and an auxiliary building sits in the southwest corner. In the center, a 1.5-meter high inner wall with red wooden gates surrounds the altars: square stone platforms a meter or so off the ground and topped with dirt. The barrenness of the altars makes them seem somehow either even more ancient than they actually are or fake, like cheaply made replicas of a long ago ceremonial site that anthropologists don’t fully understand. As it is, however, they’re still functional, if only in a symbolic sense – each National Foundation Day (October 3), descendants of the royal Jeonju Yi clan perform the traditional rites, which they revived in 1988.

In truth, there’s not much to see. A three-part stone walkway zig-zags across a broad lawn from the north to the west gate, and an auxiliary building sits in the southwest corner. In the center, a 1.5-meter high inner wall with red wooden gates surrounds the altars: square stone platforms a meter or so off the ground and topped with dirt. The barrenness of the altars makes them seem somehow either even more ancient than they actually are or fake, like cheaply made replicas of a long ago ceremonial site that anthropologists don’t fully understand. As it is, however, they’re still functional, if only in a symbolic sense – each National Foundation Day (October 3), descendants of the royal Jeonju Yi clan perform the traditional rites, which they revived in 1988.

Within the park’s grounds and west of the altars is a large dirt expanse with badminton, basketball, and croquet courts, a group of old folks making use of the last one. There are also two towering statues at either end: to the south is the Confucian scholar 이율곡 (Yi Yul-gok), a scroll in his right hand, his left resting atop a stack of books, and to the north is his mother, the scholar and artist 신사임당 (Shin Saimdang).

If you continue following the curve of Sajik-ro past the park’s entrance you’ll soon come to Inwangsan-ro (인왕산로) on your right, where signs point to the Inwangsan Trail (인왕산산책로) and Seoul Fortress Wall (서울성곽). Well before you get to either of those, however, the road elevates quickly and brings you to Dangun Shrine (단군성전). Opposite an army base and marked by a sign that just says ‘Tangun,’ the shrine is dedicated to Dangun Wanggeom (단군왕검), the founder of the Gojoseon dynasty in 2333 B.C. and the son of the divine Hwanung and Ungnyeo, that steadfast bear who was turned into a human by fulfulling her promise to pass 100 days out of the sun eating nothing but 20 cloves of garlic and some mugwort. Built in 1968 with donations from a trio of sisters, it includes a portrait and a statue of Dangun, who, with his stout frame, broad nose, and thick black facial hair, takes after his mother. Two candles and bottles of water and liquor rested on a small altar in front. Ceremonies celebrating the ascension of Dangun and his founding of Korea are held here in March and October.

If you continue following the curve of Sajik-ro past the park’s entrance you’ll soon come to Inwangsan-ro (인왕산로) on your right, where signs point to the Inwangsan Trail (인왕산산책로) and Seoul Fortress Wall (서울성곽). Well before you get to either of those, however, the road elevates quickly and brings you to Dangun Shrine (단군성전). Opposite an army base and marked by a sign that just says ‘Tangun,’ the shrine is dedicated to Dangun Wanggeom (단군왕검), the founder of the Gojoseon dynasty in 2333 B.C. and the son of the divine Hwanung and Ungnyeo, that steadfast bear who was turned into a human by fulfulling her promise to pass 100 days out of the sun eating nothing but 20 cloves of garlic and some mugwort. Built in 1968 with donations from a trio of sisters, it includes a portrait and a statue of Dangun, who, with his stout frame, broad nose, and thick black facial hair, takes after his mother. Two candles and bottles of water and liquor rested on a small altar in front. Ceremonies celebrating the ascension of Dangun and his founding of Korea are held here in March and October.

Follow Inwangsan-ro further as it climbs uphill and you’ll arrive at Hwanghakjeong (황학정), a Joseon-era archery range that is Seoul Tangible Cultural Property No. 25. As guns replaced bows and arrows in the Joseon arsenal, a transformation that was complete by 1894, the bow arbors that had been cultivated mostly disappeared. King Gojong’s belief that archery fostered both a healthy mind and body made sure that its practice continued, however, and in 1898 he founded Hwanghakjeong just north of Gyeonghui Palace. Not even archery ranges were exempt from Japanese rearrangement, though, and in 1922 it was moved to its current site to make way for the Monopoly Bureau of the Japanese Governor-General.

Today Hwanghakjeong is the only remaining of five original ranges within the city walls. It continues to serve as an active range, and when I reached the shooting platform at the top, six retirees were taking practice, using traditional bows to launch arrows across a ravine. Just behind them and overlooking a view of downtown in the distance was the actual Hwanghak pavilion, a large wooden viewing pavilion with a portrait of King Taejo and a Korean flag up on its back wall. There were a few plastic seats out front, and I took a seat in one to watch for a bit.

At the far end of the range a red, yellow, and blue windsock alternated between an emphatic pointing and a weak nod as the wind gusted and subsided. Released from the bows, the arrows wiggled slightly as they flew across the ravine, like tadpoles propelling themselves forward. Their targets, perhaps a hundred meters distant, were three white boards with black squares holding red circles, in the center of which were white horizontal lines like on a Do Not Enter sign. One of the targets had a single white bar, another had two, and the third had three, though all were set up alongside each other at the same distance. From the viewing platform they looked small, but when the round was over and one of the archers went across the ravine and stood next to them while picking up the spent arrows they were suddenly revealed to be easily larger than him, perhaps two meters by two meters. When he had collected all the arrows the man placed them in a rectangular metal box and an electric pulley cabled them back up to the shooting gallery for the next round.

The neighborhood between these sites and the palace is known as Seochon (서촌), ‘Western Village,’ and it’s an area of the city that’s been occupied probably about as long as the city’s been occupied. While Bukchon grabs the bulk of the tourist headlines for its picturesque hanok, one-fifth of the city’s traditional homes can be found here, and whereas a walk through the neighborhood east of Gyeongbokgung can sometimes have the feel of a walk through Olde Tyme Seoul, presented by Lotte, Seochon remains an area that, while not untouched by tourism, is relatively unexplored and decidedly local. It has a number of relatively obscure attractions hidden within, but equally rewarding to searching them out is simply throwing away the map and spending an afternoon wandering its nooks and crannies.

The neighborhood between these sites and the palace is known as Seochon (서촌), ‘Western Village,’ and it’s an area of the city that’s been occupied probably about as long as the city’s been occupied. While Bukchon grabs the bulk of the tourist headlines for its picturesque hanok, one-fifth of the city’s traditional homes can be found here, and whereas a walk through the neighborhood east of Gyeongbokgung can sometimes have the feel of a walk through Olde Tyme Seoul, presented by Lotte, Seochon remains an area that, while not untouched by tourism, is relatively unexplored and decidedly local. It has a number of relatively obscure attractions hidden within, but equally rewarding to searching them out is simply throwing away the map and spending an afternoon wandering its nooks and crannies.

Seochon is roughly bisected into eastern and western halves by Jahamun-ro (자하문로), which, like the character of the neighborhoods surrounding it, balances traditional shops with modern boutiques.

Seochon is roughly bisected into eastern and western halves by Jahamun-ro (자하문로), which, like the character of the neighborhoods surrounding it, balances traditional shops with modern boutiques.

If you leave Exit 2 the first left, Jahamun-ro-1-gil (자하문로1길) takes you into Sejong Village Food Street (세종마을음식문화거리), a narrow alley lined with restaurants. While many food streets in Seoul are dedicated to a particular dish, Sejong is far more omnivorous, with gopchang and jokbal places, galbi barbecues, bunsiks, pojangmachas, a french fry stall, and a pizza place with Seochon microbrews on tap. Between the eateries are florists, small produce stalls, salons, boutiques, and an LP bar. Busy even on a Tuesday afternoon, its customers are a mix of neighborhood old timers, students from the nearby women’s university, local residents, and area art gallery hoppers, and it’s maybe partly due to the diverse clientele that the more modern eateries seem to mesh well with the older establishments.

Continuing north, just past Jahamun-ro-9-gil (자하문로9길) is a small stone plaque with just four lines of text on it. In a country with the man on its money and in its main square, this is all there is to mark the Birthplace of King Sejong (세종대왕나신곳). Born here in 1397, the site is now occupied by a glasses shop.

Continuing north, just past Jahamun-ro-9-gil (자하문로9길) is a small stone plaque with just four lines of text on it. In a country with the man on its money and in its main square, this is all there is to mark the Birthplace of King Sejong (세종대왕나신곳). Born here in 1397, the site is now occupied by a glasses shop.

A bit further on, passing one truck selling bundles of whole garlic and another selling all manner of traditional woven straw goods, I arrived at Tongin Market (통인시장), marked by a large stone and wood entrance on Jahamun-ro-15-gil (자하문로15길). Founded as a market for Japanese residents in 1941, Tongin is one of those markets in Seoul that have gotten a makeover in an attempt to modernize them and keep them vibrant and relevant in a time when giant supermarkets and chain stores threaten their existence. At Tongin this has been done by cleaning it up and by trying to create a nostalgic link to the past. Banners featuring traditional striped designs or pictures of tigers are strung overhead, catching the light that filters through the translucent arched ceiling, and in the center of the market a wall is covered by the Tongin Market Story Map (통인시장이야기지도), which has small profiles of all the market stalls and their operators. Alongside it a larger map of the neighborhood spotlights local sights and the stories behind some of them.

In another nod toward modernization, some of the market stalls are taken up by trendy clothing boutiques of the sort that you might find in Bukchon, but Tongin’s focus and its two main draws are rooted in its food. One of these is oil tteokbokki (기름떡볶이), and I sat down for some at the first place in the market to do it, 원조할머니떡볶이 (Original Grandma Tteokbokki). Basically, gireum tteokbokki is simply tteokbokki that’s been cooked in a thicker than usual sauce and then stir-fried in oil for a bit, and the result is something that tastes a bit like the pieces of rice cake in dalk galbi. It’s good, though I’m not sure it’s good enough to warrant a trip on its own. Much cooler is the innovative dosirak, or lunchbox, program that’s been started at Tongin. For a few bucks you get a tray and a few tokens (in the form of antique Korean coins) which you can then take around from stall to stall and redeem for a bit of this and a bit of that, fixing yourself an a la carte lunch, a fun and innovative spin on the market experience.

The neighborhood between Jahamun-ro and Pirundae-ro (필운대로), at the opposite end of both Tongin Market and Sejong Village Food Street, is a quiet, mostly residential area, with the occasional boutique, architect’s studio, or restaurant in a restored hanok signs of the gentrification slowly evolving its character.

The neighborhood between Jahamun-ro and Pirundae-ro (필운대로), at the opposite end of both Tongin Market and Sejong Village Food Street, is a quiet, mostly residential area, with the occasional boutique, architect’s studio, or restaurant in a restored hanok signs of the gentrification slowly evolving its character.

Cutting diagonally through the heart of the neighborhood is Jahamun-ro-7-gil (자하문로7길), a mixture of old buildings and businesses and new cafes and Italian restaurants. Slightly closer to the Pirundae-ro end is one of the most interesting and most charming structures on the street, and one that encapsulates both the neighborhood’s nostalgia for the past and its tendency towards modern trendiness: Dae-oh Bookstore (대오서점). Opened in 1951, the tiny little shop took its name after the middle characters in the names of the husband and wife who founded it. Perhaps predictably for a mom and pop bookstore on an old side street, Dae-oh wasn’t able to stay in business, but thanks to local support the building at No. 55 Jahamun-ro-7-gil has been maintained, tattered sign and all, as a time capsule cum café.

The ramshackle little building that houses Dae-oh sits under an old-fashioned tile roof, and above its light blue door is a sign on which the shop’s name is spelled out in simple black letters on a white background. Under the name is the store’s old phone number, 735-134 , the last digit missing, having peeled off along with much of ‘서점’ some time in the past. On a small table in front of the door a variety of postcards are offered for sale on the honor system.

Inside, a tiny coffee bar has been set up in the old book room, and both there and in parts of the building’s former living quarters there is seating for patrons, mostly in the form of old school desks and chairs. Figurines, photos, posters of a drama that the shop appeared in, and other memorabilia from the bookstore’s and its owners’ lives decorate the interior, but the greatest amount of space is for the hundreds of books that, once for sale, now serve as a snapshot of what Dae-oh once was. Many books fill shelves around the edges of the hanok’s courtyard, and even more are crammed into the tiny room just inside the shop’s old front door. There, floor to ceiling shelves are jammed full of hardbacks and paperbacks, a series of children’s biographies among them (Washington, Mozart, Florence Nightingale), and those that don’t fit are stacked in piles on the floor.

Once I reached the west end of Jahamun-ro-7-gil, I turned right onto Pirundae-ro and headed north. Here and there trucks parked on corners were selling fruit or dried shrimp in huge bags while recorded sales pitches came out of their speakers. Not far past Tongin Market there was a marker in the sidewalk noting the site of Jasu Palace (자수궁터), built in 1616 by Gwanghaegun, the 15th Joseon king. Now it was apartment blocks and a small playground. The further north I went the better the views of Inwang Mountain I was treated to and the pricier the housing appeared to get; a Maserati and more than one Audi drove by.

Where the road made a curving turn to the east I came to Woodang Memorial Hall (우당기념관), which commemorates우당이회영 (Woodang Yi Hoeyeong), an anarchist and independence activist. The son of nobility, Yi and several of his brothers went into self-imposed exile in China after the Japanese annexed Korea. There he both founded the Sinheung Military Academy in Manchuria and participated in the Korean Provisional Government, based in Shanghai. He died in Japanese custody in 1932.

Across the street from the memorial hall are the Wall Paintings of Seoul National School for the Deaf and the Blind (국립서울농–맹학교담장벽화), al fresco artworks by students of those schools that are worth a look if you’re in the area. One section consists of pastel tiles of raised handprints that are paired with brief messages in braille, Korean translations next to them. Another shows student drawings that alternate with panels displaying the hand positions for numbers and letters in Korean sign language.

East of Jahamun-ro and squeezed between it and the palace is the atmospheric Tongui-dong (통의동), peppered with hanoks, galleries, and interesting little historical spots. For a walking tour of some of its most picturesque spots, start by heading north from Exit 3 and turning right on Jahamun-ro-4-gil (자하문로4길), then taking the first alley on your left. This will bring you to a small courtyard between apartments and a restaurant, in the center of which is the Tongui-dong White Pine Site (통의동백송터), which once boasted the country’s largest white pine – 16 meters tall and five meters in diameter. Formerly Natural Monument No. 4, it was felled by a typhoon in 1990 and only the lower part of the trunk remains. Surrounding the trunk, however, are four young white pines, which a sign says descended from the original. Their skin is a mottled gray, pale green, and dark green that looks uncannily like camouflage. A couple dozen kimchi pots rest on the ground beneath them.

East of Jahamun-ro and squeezed between it and the palace is the atmospheric Tongui-dong (통의동), peppered with hanoks, galleries, and interesting little historical spots. For a walking tour of some of its most picturesque spots, start by heading north from Exit 3 and turning right on Jahamun-ro-4-gil (자하문로4길), then taking the first alley on your left. This will bring you to a small courtyard between apartments and a restaurant, in the center of which is the Tongui-dong White Pine Site (통의동백송터), which once boasted the country’s largest white pine – 16 meters tall and five meters in diameter. Formerly Natural Monument No. 4, it was felled by a typhoon in 1990 and only the lower part of the trunk remains. Surrounding the trunk, however, are four young white pines, which a sign says descended from the original. Their skin is a mottled gray, pale green, and dark green that looks uncannily like camouflage. A couple dozen kimchi pots rest on the ground beneath them.

Continue to the opposite end of the alley, turn right on Jahamun-6-gil (자하문6길), and then left on Hyoja-ro-7-gil (효자로7길), just after Gallery Artside. Just a few steps up on your left will be a tiny entrance that leads into one of the most picturesque alleys in the city.

There’s no formal name for it, and Naver Maps doesn’t even list a street name, so for lack of a better term we’ll just call it Tongui-dong Hanok Alley. Although the alley isn’t lined entirely with hanoks and although some of those that are here have been turned into wine bars or restaurants or guesthouses, it’s one of the exceedingly few places in Seoul where it seems as if the past century never happened.

The alley is narrow enough in places to touch both walls at the same time, and it zigzags back and forth in a series of ninety-degree angles so that it never reveals too much of itself, leaving you to focus on and savor each touch of beauty in its tight frame. Shoots of bamboo line one part of the alleyway; dandelions grow in the spaces between rooftop tiles; white-tipped wooden roof beams extend outward, the eaves of opposing homes only two feet apart in spots; solid double wooden doors are ornamented with images of gates in black or silver metal, half the decoration on either door, coming together only when they’re closed for the night.

When I walked down the alley I was utterly alone, something that would never happen in Bukchon. Surrounded by so much history in this part of town, it was here that I felt I got perhaps the closest to a sense of what the city was like in the late Joseon era. One home was open, the metal gate on its front doors split in two and flung open, and I was able to peer into the hanok’s courtyard. Window panes were divided by polished wood into traditional square and rectangle patterns, and an elevated platform separated the courtyard from the living quarters. Resting on top of it was a pair of maroon boat shoes, a sign of the modern life lived inside.

Gyeongbokgung Palace (경복궁)

Exit 5

02) 3700-3900

Hours | March – May, September – October 9:00 – 18:00; June – August 9:00 – 18:30; November – February 9:00 – 17:00; Closed Tuesdays

Admission | Adults 3,000; Kids 7-18 1,000; Under 7 and 65+ free; Combo ticket for Gyeongbokgung, Changdeokgung, Changgyeonggung, Deoksugung, and Jongmyo 10,000/5,000 for adults, kids (valid for 1 month)

National Palace Museum of Korea (국립고궁박물관)

Exit 5

02) 3701-7500

Hours | Tuesday – Friday 9:00 – 18:00, Weekends and Holidays 9:00 – 19:00; Closed Mondays unless Monday is a national holiday

Admission | Free

National Folk Museum of Korea (국립민속박물관)

Exit 5

02) 725-4503, 02) 3704-3114

Hours | March – May, September – October 9:00 – 18:00; June – August 9:00 – 18:30; November – February 9:00 – 17:00; Closed Tuesdays

Admission | Free

Dongsipjagak (동십자각)

Exit 4

U-turn, Straight on Sajik-ro (사직로)

Cheongwadae (청와대)

Exit 4

U-turn, Left on Hyoja-ro (효자로), Right on Cheongwadae-ro (청와대로)

Cheongwadae Sarangchae (청와대사랑채)

Exit 4

U-turn, Left on Hyoja-ro (효자로)

Hours | 9:00 – 18:00, Closed Mondays

Admission | Free

Mugunghwa Park (무궁화공원)

Exit 4

U-turn, Left on Hyoja-ro (효자로), Left after Cheongwadae Sarangchae (청와대사랑채)

Yuksanggung Shrine (육상궁)

Exit 4

U-turn, Left on Hyoja-ro (효자로), Left after Cheongwadae Sarangchae (청와대사랑채), Right on Changuimun-ro (창의문로)

Government Complex Seoul (정부서울청사)

Exit 6

U-turn, Right on Sejong-daero (세종대로)

Gwanghwamun Plaza (광화문광장)

Exit 6

U-turn, Right on Sajik-ro (사직로), Straight on Sajik-ro (사직로)

Sejong-ro Park (세종로공원) and the Former Site of the Byeongjo (병조터)

Exit 6

U-turn, Right on Sajik-ro (사직로), Right on Sejong-daero (세종대로)

Hangeul-gaon-gil (한글가온길) and the Former Site of Jangheunggo Office (장흥고터)

Exit 7

U-turn, Right on Saemunan-ro-3-gil (새문안로3길)

Sajik Park (사직공원) and Sajik Altar (사직단)

Exit 1

Straight on Sajik-ro (사직로)

Dangun Shrine (단군성전)

Exit 1

Straight on Sajik-ro (사직로), Right on Inwangsan-ro (인왕산로)

blog.naver.com/lgb301

Hwanghakjeong (황학정)

Exit 1

Straight on Sajik-ro (사직로), Right on Inwangsan-ro (인왕산로)

Sejong Village Food Street (세종마을음식문화거리)

Exit 2

Left on Jahamun-ro-1-gil (자하문로1길)

Birthplace of King Sejong (세종대왕나신곳)

Exit 2

Straight on Jahamun-ro (자하문로)

Tongin Market (통인시장)

Exit 2

Straight on Jahamun-ro (자하문로), Left on Jahamun-ro-15-gil (자하문로15길)

tonginmarket.co.kr

Hours | Weekdays 9:00 – 18:00, Saturdays 9:00 – 13:00, Closed Sundays and holidays

Dae-oh Bookstore (대오서점)

Exit 2

Straight on Jahamun-ro (자하문로), Left on Jahamun-ro-7-gil (자하문로7길)

Woodang Memorial Hall (우당기념관)

Exit 2

Straight on Jahamun-ro (자하문로), Left on Pirundae-ro (필운대로)

Wall Paintings of Seoul National School for the Deaf and the Blind (국립서울농–맹학교담장벽화)

Exit 2

Straight on Jahamun-ro (자하문로), Left on Pirundae-ro (필운대로)

Tongui-dong White Pine Site (통의동백송터)

Exit 3

Jahamun-ro-4-gil (자하문로4길), Left on first alley

Tongui-dong Hanok Alley

Exit 3

Right on Jahamun-6-gil (자하문6길), Left on Hyoja-ro-7-gil (효자로7길), Left on first alley

Amazing photos! I miss Seoul. Thanks for sharing its beauty!

Thank you and glad you enjoyed the photos!

Pingback: SEOUL Weekly: Goodreads Book Giveaway: Across the Tumen | SEOUL Magazine

Pingback: Seoul Forest Station (서울숲역) Bundang Line – Station #K211 | Seoul Sub→urban

You described the places so beautifully and with so much detail; I felt like I was walking with you at that very moment. Your photos are beyond amazing! Thank you so much for sharing all these wonderful tidbits about Seoul – truly a big help for our upcoming trip!

You’re so welcome! I hope you enjoy the city!

we thoroughly enjoyed our trip! can’t wait to go back!